In the old days, before the missionaries came with their bells and their books, before the world changed and the ancient ways began to fade like footprints washed away by the tide, certain people in the Banks Islands possessed a power both terrible and forbidden. These were not ordinary men and women. They were not chiefs or warriors or healers. They were something darker, something that existed in the shadowy space between the world of the living and the realm of the dead.

They were called the Talamaur.

The word itself was whispered, never spoken loudly in the bright hours of daylight. Parents would hush their children if they said it carelessly. Elders would glance over their shoulders before uttering it, as if the very sound might summon something best left undisturbed. For the Talamaur were not merely sorcerers or magic workers they were people who had learned to rule the spirits of the dead, to bind ghosts to their will and command them like servants or slaves.

Click to read all Melanesian Folktales — rich oral storytelling from Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu

The path to becoming a Talamaur was not one that could be learned from teachers or passed down through families like the knowledge of canoe-building or the art of weaving. It was a dark road that a person chose to walk alone, driven by hunger for power or by desires that went beyond the natural limits of human life. And the first step on that path required an act so transgressive, so utterly forbidden by every custom and taboo, that even to speak of it brought unease.

When someone in the village died whether from sickness, accident, or old age the body would be prepared according to tradition. The family would wash the corpse, anoint it with oils, wrap it in bark cloth or mats. They would mourn with wailing and tears, and eventually, the body would be laid to rest in the prescribed manner. But during this time, when the family kept vigil and the community gathered to honor the dead, the Talamaur would wait and watch.

In secret, under cover of darkness when the mourners had finally succumbed to exhausted sleep, the Talamaur would approach the corpse. What happened next violated every sacred law, every fundamental boundary that separated the living from the dead, the profane from the sacred. The Talamaur would eat a piece of the corpse sometimes a finger, sometimes a portion of flesh from the arm or leg. It was not done from hunger or madness, but with cold purpose and terrible intent.

For in that act of consuming the dead, the Talamaur forged an unbreakable bond with the ghost of the deceased. The spirit, newly released from its body and confused in its transition between worlds, became trapped bound to the will of the one who had consumed its flesh. It could not move on to the land of the ancestors. It could not rest. It became, instead, a tool, a weapon, an extension of the Talamaur’s dark will.

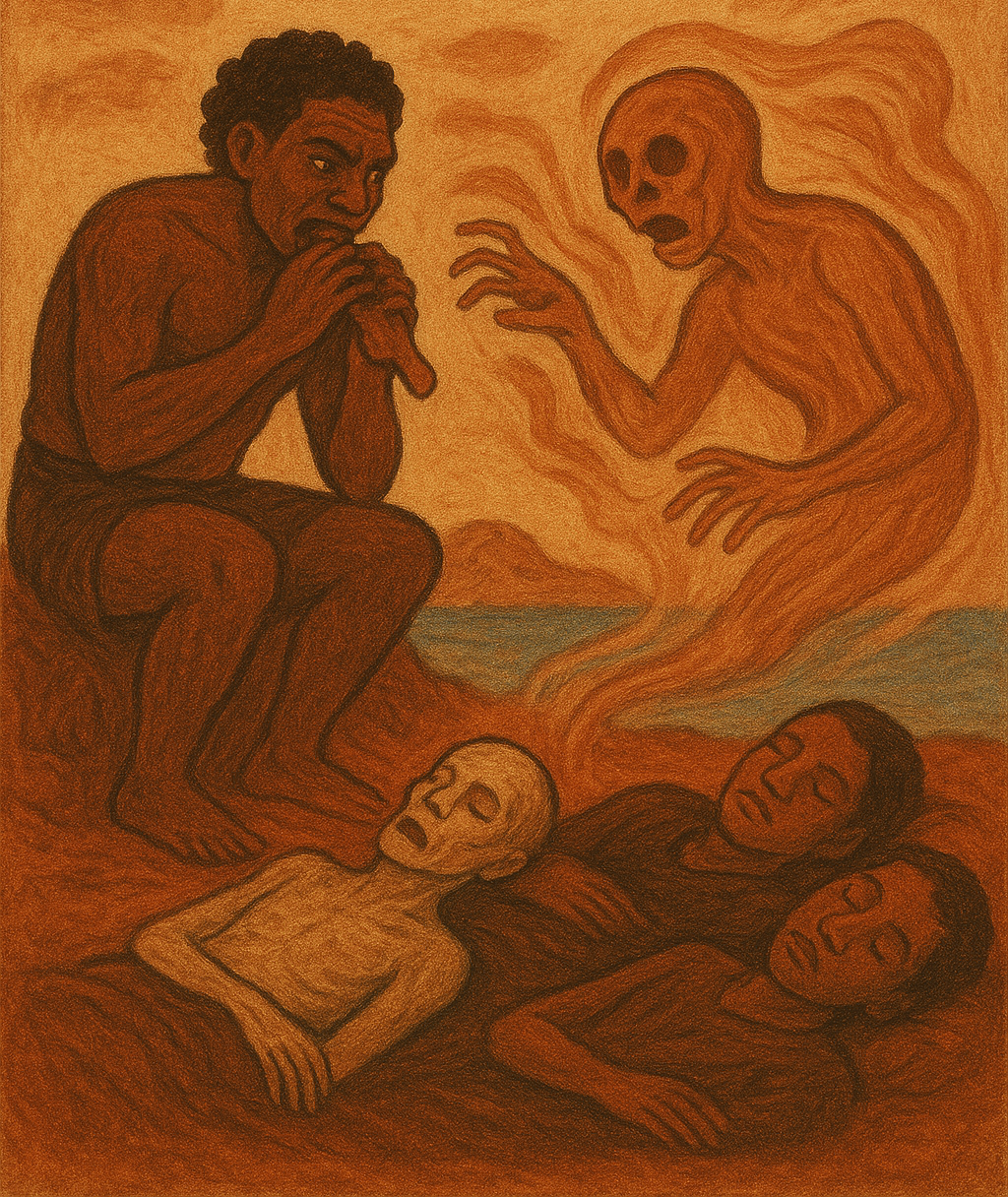

At night, when honest people slept peacefully in their homes, when the cooking fires had burned down to embers and the island lay quiet beneath the stars, the Talamaur would send forth his ghost. The spirit would glide through the darkness like mist, passing through walls and beneath doorways, moving with the terrible silence of the dead. It would find its victim someone the Talamaur had chosen, perhaps an enemy, perhaps someone who possessed something the Talamaur desired, or perhaps simply someone whose life force seemed particularly strong and vital.

The ghost would hover over the sleeping person, drawn to the warmth of living breath, to the pulse of blood through veins, to the spark of life that still burned bright. And then, with a hunger born of its own frustration at being trapped between worlds, the ghost would begin to feed. It would suck the life essence from the sleeper, draining away their strength, their vitality, their very will to live. The victim would not wake they would simply lie there as their life force was slowly, inexorably drawn away into the hungry void.

Night after night, this feeding would continue. The ghost would return again and again, each time taking more, and all that stolen strength would flow back along the invisible cord that bound it to the Talamaur. The sorcerer would grow stronger, more vital, filled with an energy that was not truly his own but stolen from others like water drawn from a well.

But there was a price. There is always a price when one traffics with death and breaks the fundamental laws that govern the boundary between living and dead.

The Talamaur’s own spirit would begin to weaken. Even as his body grew strong with stolen life force, his essential self his soul, his true nature would start to fade and fray like old cloth left too long in the sun. He would become less human with each passing moon, more like the ghosts he commanded, caught between worlds, belonging fully to neither. His eyes would take on a strange quality, as if they were looking at things others could not see. His presence would make people uneasy without quite knowing why. And always, always, there would be a coldness about him, as if death itself had touched him and left its mark.

Meanwhile, the victims of the ghost’s feeding would exhibit signs that everyone recognized with dread. A person who had been healthy and strong would begin to grow thin. Their skin would become pale, almost translucent, like rice paper held up to the light. They would complain of exhaustion, of dreamless sleep that brought no rest. Their eyes would seem to sink back into their skulls. Their strength would drain away like water leaking from a cracked pot, and yet no doctor could find any illness, no healer could identify any disease.

When such symptoms appeared, people would gather in small groups and talk in low voices. They would glance nervously at certain members of the community, weighing suspicions, remembering old grudges or strange behaviors. And eventually, someone would whisper the words that everyone had been thinking but no one wanted to say aloud: “A Talamaur feeds upon him.”

The accusation, once spoken, would spread through the village like fire through dry grass. Fear would take hold. Trust would erode. People would eye each other suspiciously, wondering who among them had chosen to walk the dark path, who had bound the dead to their will and was now draining life from the living.

Sometimes the victim would waste away and die, their life completely consumed. Sometimes a powerful healer or another sorcerer would intervene, breaking the ghost’s hold and forcing it to release its prey. And sometimes, the community would turn on the suspected Talamaur, driving them out or worse, ensuring that their own power would destroy them in the end.

For the truth that every Talamaur eventually learned—though by then it was too late was that commanding spirits is not true power at all, but a slow form of suicide. To bind the dead is to become like them, to sacrifice one’s own humanity bit by bit until nothing remains but a hollow shell, neither living nor dead, feared by all and belonging to none.

The years passed. The world changed. New beliefs came to the islands, bringing different understandings of death and spirit, of power and taboo. The old ways faded, and the practice of the Talamaur if it ever truly existed as described, or if it was always partly legend, partly warning disappeared into history.

But even now, even in these modern times when the young people go to schools and use phones and speak of the old stories as if they were merely fairy tales, the elders remember. They know the word. They understand what it meant and what it represented. And when they speak of the Talamaur, there is still that edge of wariness in their voices, that glance over the shoulder, that acknowledgment of something that perhaps should not be entirely forgotten.

For the tale of the Talamaur is more than just a story. It is a reminder that exists in the very language itself a warning carved into the collective memory of the people. It speaks to the dangerous allure of power, especially power gained through transgression. It reminds us that every ability comes with responsibility, every gift with a cost, and every boundary exists for a reason.

To command spirits, the story tells us, is to walk the edge between the living and the dead. And those who walk such edges must not be surprised when they eventually fall.

Explore tales of ancestral spirits and island creation that connect people to the land and sea

The Moral Lesson

This haunting tale teaches that pursuing power through forbidden means always exacts a terrible price. The Talamaur gained the ability to command ghosts and drain others’ life force, but in doing so, they sacrificed their own humanity and spiritual wellbeing. The story warns against transgressing sacred boundaries and reminds us that true strength comes not from dominating others or the natural order, but from living in harmony with the proper limits that protect both individuals and communities. Some powers are forbidden not because they don’t work, but because the cost of using them is too high.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What is a Talamaur in Banks Islands mythology and what power did they possess?

A: A Talamaur was a spirit master in Banks Islands culture who could rule the ghosts of the dead. They bound spirits to their will by secretly consuming part of a corpse, then commanded these ghosts to drain life force from sleeping victims, feeding on their strength and vitality.

Q2: How did someone become a Talamaur according to this Melanesian legend?

A: To become a Talamaur, a person had to perform a forbidden act secretly eating a portion of a deceased person’s body. This transgressive ritual created an unbreakable bond between the Talamaur and the ghost of the dead, allowing the sorcerer to control and command the spirit.

Q3: What were the signs that someone was being attacked by a Talamaur’s ghost?

A: Victims would become mysteriously thin and pale without any identifiable illness. They would grow weak and exhausted despite sleeping, their strength draining away progressively. These symptoms occurred because a ghost was sucking their life force away at night while they slept.

Q4: What price did the Talamaur pay for their power over spirits?

A: While the Talamaur gained stolen life force and grew physically stronger, their own spirit would weaken and fade. They would become less human over time, caught between the world of the living and the dead, ultimately sacrificing their humanity and spiritual wellbeing for their dark power.

Q5: What does this Pacific Islands legend teach about forbidden power and boundaries?

A: The story teaches that transgressing sacred boundaries to gain power always comes with a devastating cost. It warns that some abilities should remain forbidden not because they’re impossible, but because using them destroys the user. The tale emphasizes respecting the natural separation between life and death.

Q6: Why do elders say the word “Talamaur” still matters today?

A: Even though the practice has faded, the word serves as a cultural reminder embedded in the community’s collective memory. It functions as a lasting warning about the dangers of seeking power through forbidden means and the importance of respecting boundaries between the living and the dead, ensuring these lessons aren’t forgotten.

Source: Adapted from The Melanesians: Studies in Their Anthropology and Folklore by R.H. Codrington (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1891).

Cultural Origin: Melanesian belief system, specifically from the Banks Islands, northern Vanuatu, Pacific Ocean. This represents traditional indigenous spiritual concepts regarding death, spirits, and taboo practices.