In the days when the boundary between land and sea remained as soft as morning mist, there lived in Lau Lagoon a girl named Meli. She was gentle as the dawn the kind of gentleness that comes not from weakness but from a heart that chooses kindness even when the world offers cruelty in return. Her village clung to the edge of Malaita Island, where houses stood on stilts above the water and canoes rocked against weathered posts like children against their mothers’ hips.

Meli’s hands were never idle. She wove mats from pandanus leaves, her fingers moving with the rhythm of waves against coral, creating patterns that told stories without words. The mats she made carried the sweet, grassy scent of the plant, and when people laid them out in their homes, the fragrance reminded them of sunshine and wind, of the living world brought indoors. Her laugh was like wind moving through reed beds light and musical, a sound that made others smile without knowing quite why, a sound that belonged to the lagoon as much as the call of seabirds or the splash of fish.

Click to read all Melanesian Folktales — rich oral storytelling from Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu

But Meli’s heart had fixed itself upon a man who did not deserve the treasure she offered. He was the kind of man who mistook cruelty for cleverness, who believed that words could be weapons without consequence. He tested her with jests that cut like coral sharp enough to wound but disguised as humor so that objecting made her seem small and unable to take a joke. He would say things that made others laugh while leaving her standing alone, uncertain whether to smile or weep. And sometimes, quite literally, he would leave her standing in the rain walking away with his friends while she waited beneath darkening skies, her presence forgotten as easily as yesterday’s tide.

Each slight was a small stone added to a weight she carried in her chest. Each dismissive word was another thread pulled from the fabric of her spirit. Meli bore this quietly, as gentle souls often do, not wanting to make trouble, hoping that patience and devotion would somehow transform his hardness into softness, his cruelty into care. But hope, when fed only disappointment, eventually withers like a plant denied water.

One afternoon, the cruelty reached a breaking point. He made a jest so sharp, so publicly humiliating, that it seemed to split the very breath from her lungs. He had taken something private something vulnerable she had shared in trust and turned it into entertainment for the gathering. The laughter that followed rang in her ears like the cries of seabirds over carrion. Some laughed uncomfortably, sensing they should not. Others laughed genuinely, not seeing or not caring about the devastation on Meli’s face.

Without a word, she turned away. Her feet carried her along the familiar path to the reef, that liminal space where the village’s claim on the world ended and the ocean’s domain began. The tide was out, leaving shallow pools that caught the afternoon light like mirrors scattered across the shore. Each pool was a small world tiny fish darting among coral formations, anemones waving their tentacles like underwater flowers, crabs scuttling sideways across rocks worn smooth by centuries of waves.

Meli walked into the shallows, the warm water rising first to her ankles, then to her knees. The sensation was familiar she had walked these shallows since childhood but today it felt different, like a greeting, like an invitation. She found a sea pond, its surface smooth as polished shell, reflecting sky and clouds and her own troubled face. She knelt in the water, feeling it embrace her legs with gentle pressure, and cupped her hands around that small mirror of ocean.

Then she whispered. She whispered all the hurt every cruel jest, every moment of waiting in the rain, every public humiliation, every private disappointment. She poured her pain into the water the way one might pour an offering to the ancestors, trusting that something would receive it, would acknowledge it, would understand.

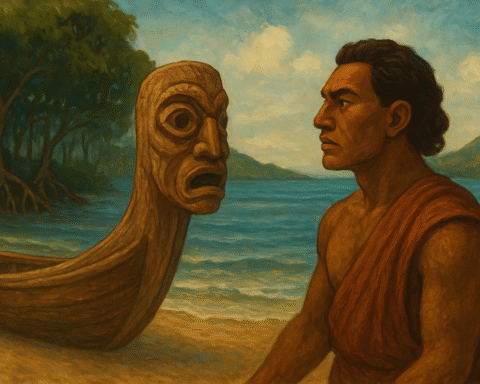

The sea heard her. The ocean, which had cradled the islands since before human memory began, which held stories older than language itself, recognized the depth of her sorrow. A voice rose from the water not heard with ears alone but felt in bone and blood and the deepest places of the heart. It was a voice like far thunder rolling across vast distances, like the deep currents that move beneath the surface where light barely penetrates.

“You are of two worlds,” the sea said to Meli. “Choose.”

Meli lifted her eyes from the pool. Behind her, she could see the shore where her village stood, where cooking fires sent smoke curling up into the sky in lazy spirals. She could hear, faintly, the sounds of village life voices calling to one another, children playing, the thump of someone pounding taro. It was the world she had always known, the world of human complications and human cruelties, of sharp words and sharper hurts.

Then she looked out at the wide blue expanse before her. The lagoon stretched toward the horizon, its surface rippling with small waves that caught the light and threw it back to the sky. It was vast and ancient and unconcerned with human drama. It asked nothing of her except that she choose. It offered no cruelty, no mockery, no jests that cut. Only movement and depth and the endless patient rhythm of tides.

With the shock of sorrow still fresh and raw in her chest, with the sound of that laughter still echoing in her ears, Meli made her choice. She let the ocean take her.

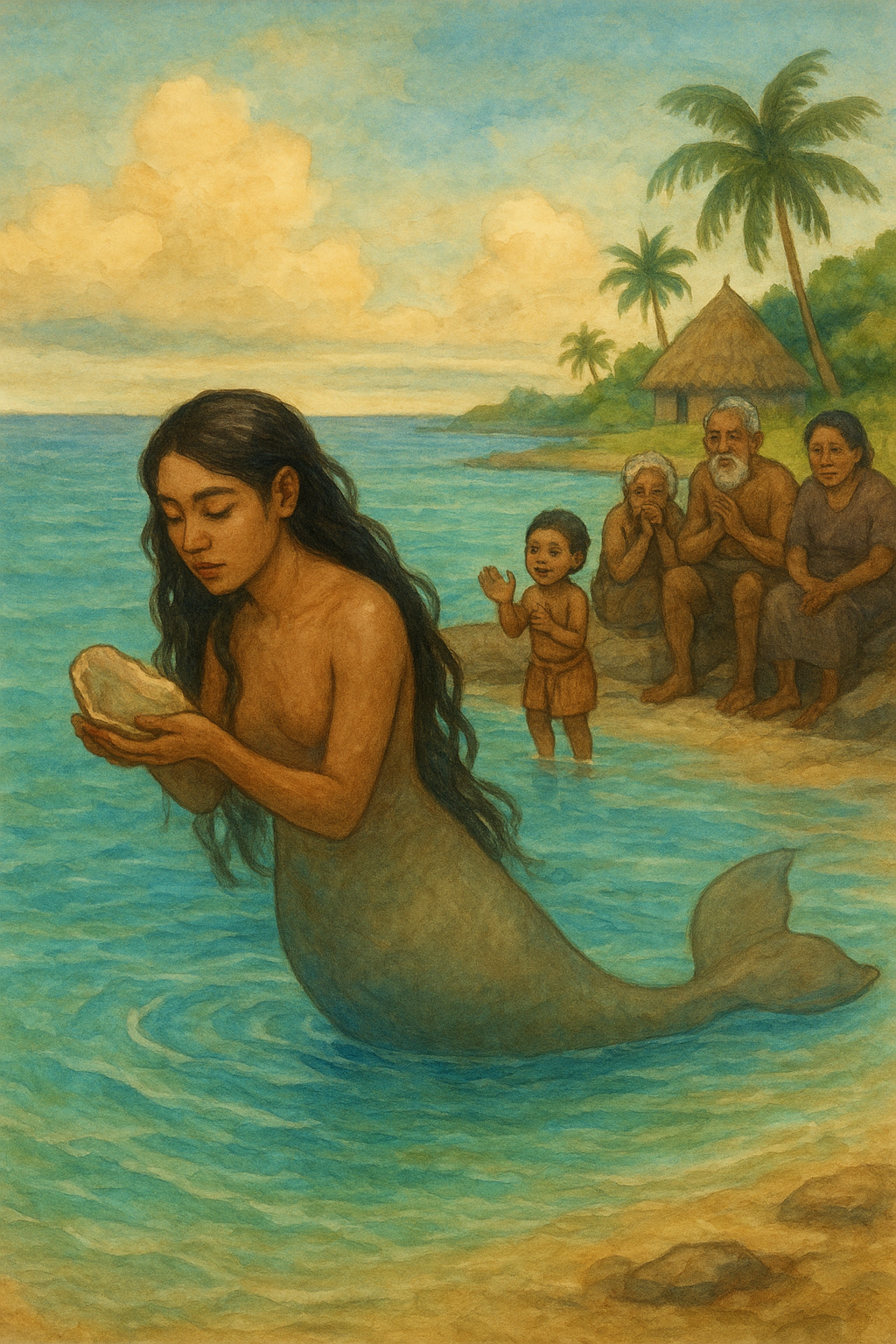

The transformation began immediately. Her legs which had walked village paths, which had stood waiting in rain, which had carried her to and from the reef countless times began to knit together. The sensation was strange but not painful, as though her body was remembering a form it had always been meant to hold but had forgotten. Her legs fused and lengthened, becoming a slow, powerful tail built not for walking on land but for gliding through water with the grace of current itself.

Her breath lengthened and deepened. Her lungs adapted, changing in ways she could feel but not name, learning to hold air for long dives into blue depths where humans could not follow. Her skin smoothed, losing the texture of air-breathing creatures, becoming sleek and perfect for the embrace of currents and the caress of water. When she dove beneath the surface for the first time in her new form, she made a sound a vocalization that was neither human speech nor animal cry but something between, something entirely her own. It was a sound like a lullaby for the fishes, soft and melodious, a greeting to her new world.

From the rocks along the shore, her family had followed her path. Perhaps they had sensed something wrong, or perhaps they had simply come looking when she disappeared. They stood watching, and when they saw what was happening saw Meli’s transformation from woman to sea creature they cried out in anguish and disbelief. Hands reached toward the water as if they could pull her back, undo what had been done, reverse time itself. Voices called her name, begging her to return, to change her mind, to come back to the world of air and earth and human love.

But among them stood a small child too young to fully understand loss, too innocent to comprehend tragedy. The child saw only wonder. Small hands clapped in delight at the round, gentle shape that moved beneath the waves with such grace and peace. The child laughed with pure joy, seeing not transformation as tragedy but as magic, as beauty, as something to celebrate rather than mourn.

The elders gathered as the sun began its descent, painting the lagoon in shades of gold and crimson and deep purple. They spoke in low, serious voices, their weathered faces grave with the weight of what they had witnessed. A consensus emerged slowly, born of grief but also of understanding. With sorrow still heavy in their hearts but with recognition of what Meli’s choice meant, they declared a rule that would bind their descendants for all generations to come.

From that day forward, the clans that had loved Meli her family, her lineage, all who claimed kinship with her by blood or affection would not harm the dugong. These gentle sea creatures, with their round bodies and peaceful ways of grazing on seagrass meadows, were sacred now. One of their own had become the ocean’s soft guardian, and to harm a dugong would be to harm Meli herself, would be to violate the memory of her transformation and the pain that had driven her to it.

The rule spread through the villages of Lau Lagoon like ripples from a stone dropped in still water. It was carried on the voices of storytellers and the authority of chiefs. It became woven into the fabric of daily life as naturally as knowing which fish were good to eat and which were poisonous, as fundamental as understanding the tides and the phases of the moon. Children grew up knowing that dugongs were tabu, protected, sacred and they grew up knowing why.

Now, when sailors pass through the lagoon and see a smooth back break the surface of the water the distinctive form of a dugong grazing peacefully on the underwater meadows they lay down their spears without hesitation. They dip their heads in respect, acknowledging the presence of something more than animal, something that carries within it the memory of transformation and choice and the consequences of cruelty. The dugong passes peacefully, its slow movements stirring the water gently, disturbing nothing. The reef continues to breathe with the pulse of tides, alive and vibrant. And the village remembers remembers that the sea keeps its own transformations, that the boundary between human and ocean is not as solid as it seems, that some sorrows are too deep to be held within the confines of land and air alone.

Explore tales of ancestral spirits and island creation that connect people to the land and sea

The Moral Lesson

Meli’s story teaches us that words have the power to wound as deeply as any physical weapon, and that cruelty even when disguised as humor can drive gentle souls beyond the breaking point. The man’s thoughtless jests and public humiliations pushed Meli to seek refuge in transformation, showing us that we must treat others with care and compassion, for we never know what burdens they already carry or how close they might be to their limits. The dugong taboo that followed ensures that Meli’s pain is honored and remembered, turning personal tragedy into sacred responsibility. It reminds us that those who are transformed by suffering deserve our protection and respect, and that some losses can never be undone only honored through changed behavior in future generations.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was Meli and what were her defining characteristics in this Malaita Island legend? A: Meli was a gentle young woman from a village in Lau Lagoon, Malaita Island, described as “gentle as the dawn.” She was known for weaving beautiful pandanus mats that carried a sweet scent, and her laugh was compared to wind moving through reeds light and musical. Despite her kind nature and gentle spirit, she suffered from loving a man who treated her cruelly with sharp words disguised as jests and who would literally leave her standing in the rain while he walked away with friends.

Q2: What choice did the sea offer Meli and why did she choose transformation over remaining human? A: The sea told Meli, “You are of two worlds. Choose,” offering her the choice between remaining human on land or transforming into a sea creature. After enduring a particularly devastating public humiliation where the man she loved mocked something private and vulnerable, turning it into entertainment for others, Meli chose transformation. The ocean represented freedom from human cruelty and complications, while the village represented only pain, mockery, and a love that was never returned with respect or kindness.

Q3: How did Meli’s physical transformation into a dugong occur in the Solomon Islands legend? A: When Meli chose the ocean, her transformation was immediate and complete. Her legs knitted together and lengthened into a slow, powerful tail suited for swimming rather than walking. Her breath lengthened and deepened, her lungs adapting to hold air for long dives beneath the surface. Her skin smoothed and became sleek, perfect for moving through water. When she dove for the first time in her new form, she made a sound like a lullaby for the fishes a vocalization that was neither human nor animal but something uniquely her own.

Q4: What sacred rule did the elders establish after witnessing Meli’s transformation? A: The elders declared that from that day forward, all clans that had loved Meli her family, lineage, and anyone who claimed kinship with her would never harm dugongs. Since one of their own had become a dugong, these gentle sea creatures became sacred and protected. This taboo was woven into daily life and passed down through generations, ensuring that dugongs would be treated with respect and spared from hunting by Meli’s descendants and relatives.

Q5: How do modern sailors in Lau Lagoon honor Meli’s memory and the dugong taboo? A: When sailors pass through Lau Lagoon and see a smooth back break the surface the distinctive form of a dugong they lay down their spears immediately and dip their heads in respect. This gesture acknowledges that dugongs are more than animals; they carry within them the memory of Meli’s transformation and the pain that drove her to it. The ritual demonstrates ongoing respect for the taboo and recognition that the sea creature before them is connected to their ancestral story and family history.

Q6: What does this legend reveal about the relationship between humans and the ocean in Melanesian cosmology? A: The legend presents the boundary between human and ocean as permeable and spiritually significant rather than fixed and absolute. The sea is portrayed as a sentient force that hears prayers, responds to human suffering, and offers transformation to those in unbearable pain. The phrase “the sea keeps its own transformations” indicates that such metamorphoses are part of the natural spiritual order in traditional Melanesian belief, where humans, spirits, and nature remain deeply interconnected. The ocean serves as both refuge and alternative realm of existence for those who can no longer bear life on land.

Source: Adapted from oral traditions of Lau Lagoon communities, Malaita Island, documented in anthropological studies of Solomon Islands marine taboos and transformation legends, including references in ethnographic research on Melanesian maritime folklore and the cultural significance of dugong protection customs in Pacific Islander societies.

Cultural Origin: Lau Lagoon, Malaita Island, Solomon Islands, Melanesia