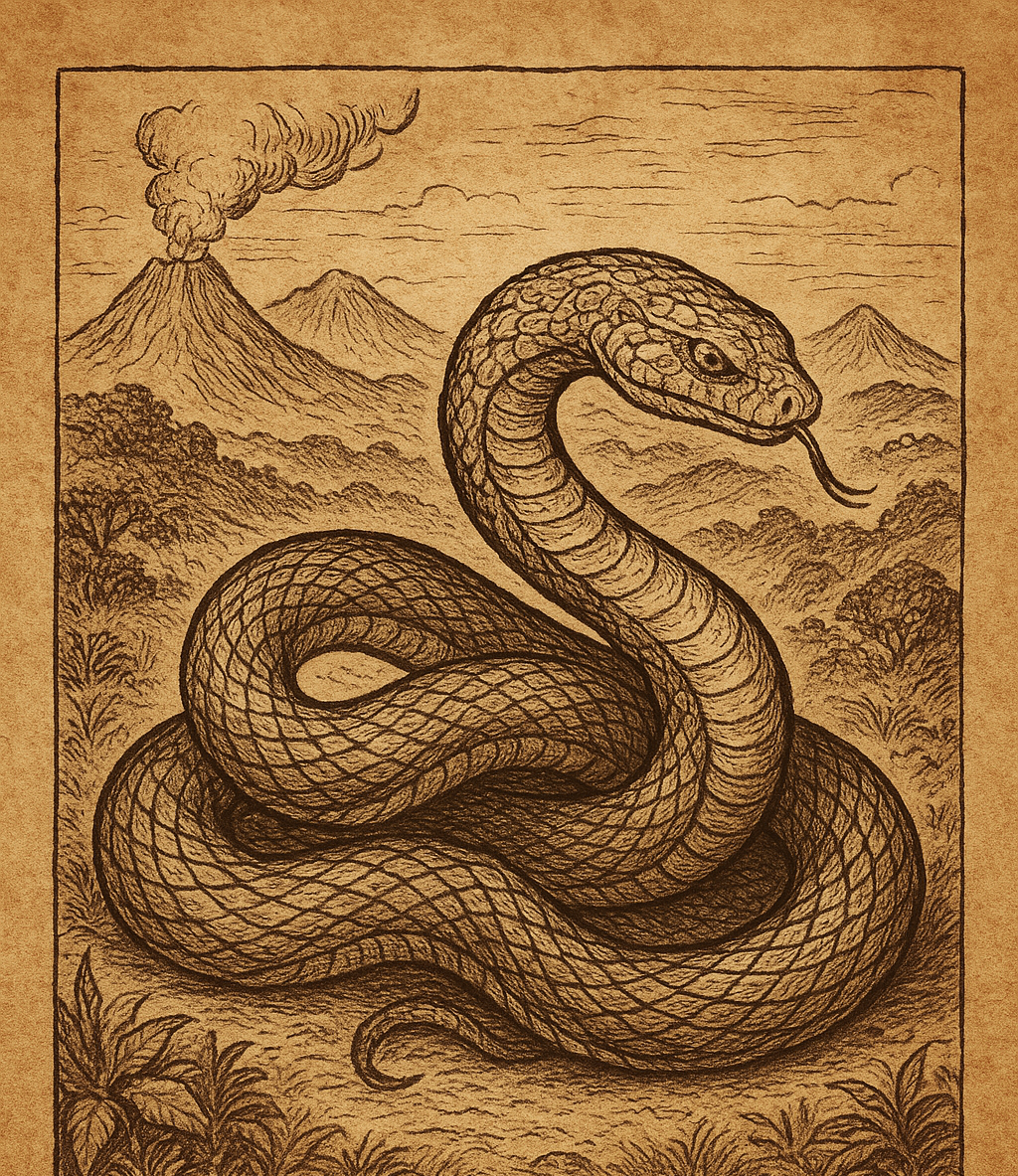

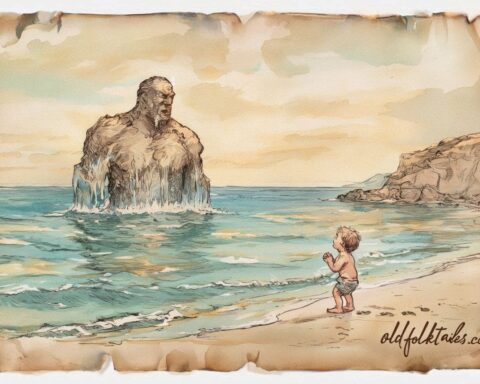

In the beginning, before the islands rose from the sea and before humans drew their first breath, there existed Degei the great serpent god, supreme creator and shaper of all that would come to be. He was no ordinary serpent, but a being of cosmic power, his body ringed with divine patterns that shimmered like the ocean under moonlight, his length so immense that no mortal eye could comprehend where he began or where he ended. Degei moved through the primordial void, ancient and alone, carrying within himself the potential for all creation.

In those earliest days, Degei was restless and active, his serpentine form gliding through the waters that covered everything. As he moved, the very landscape responded to his presence. Where his massive body coiled and turned, mountains thrust upward from the ocean floor, their peaks breaking the surface to taste the sky for the first time. Where he paused to rest, valleys formed in the impression of his curves. Where his tail dragged across the seafloor, coral reefs bloomed into existence, creating gardens of stone and color beneath the waves.

Click to read all Melanesian Folktales — rich oral storytelling from Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu

The Fijian islands themselves are the legacy of Degei’s wandering each peak and valley, each reef and lagoon shaped by the movements of the creator serpent. He did not build them with tools or conscious planning in the way humans might construct a house. Instead, the islands emerged as natural consequences of his divine presence, the earth reshaping itself to accommodate the body of a god.

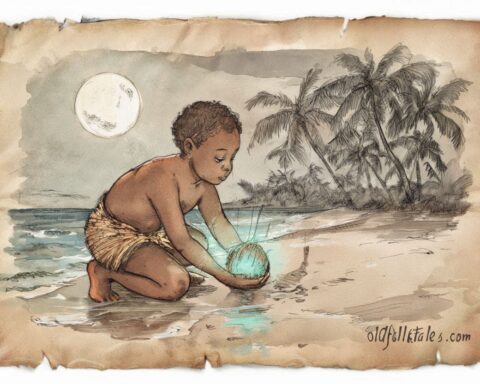

But creation was not merely geological. Once the land existed, Degei turned his attention to populating it with life. From his essence, from the power that flowed through his ringed body, he brought forth humankind the first Fijians, who would walk upon the mountains he had made and fish in the waters he had stirred. He gave them the gifts they would need to survive and thrive yams that could be cultivated to feed families through the seasons, taro with its broad leaves and starchy corms, and the knowledge of rituals that would maintain the proper relationship between the mortal and divine realms.

Degei taught the first people how to honor the gods, how to show respect to the land, and how to maintain social order through proper behavior and obligation. He established the sacred relationship between chiefs and priests, making it clear that those who held power among humans also held responsibility they must maintain correct conduct and perform the necessary ceremonies to keep the creator god favorable. When these duties were fulfilled, Degei blessed the people. When they were neglected, his displeasure could shake the very foundations of the world.

As time passed and his work of creation moved from active shaping to watchful maintenance, Degei underwent a profound transformation. The restless wanderer who had coiled across the ocean floor creating islands began to settle, to root himself in the earth he had made. His body, once freely moving through water and air, descended deeper and deeper into the ground. His massive coils wound down through soil and stone, his tail burying itself in the depths of the earth until he became not merely a god who visited the land, but a god who was the land itself a living presence within the very bones of Fiji.

From this subterranean position, Degei’s nature took on new dimensions. He remained the supreme being, the ultimate authority over all creation, but now he manifested his power differently. When Degei stirred in his earthen dwelling, when his great body shifted position or his coils tightened and relaxed, the ground trembled. What humans experienced as earthquakes were the movements of the creator god, reminders that he remained present, active, and attentive even in his coiled repose.

These earth-shakings were not always destructive, though they could be when Degei was displeased. Often, when the god moved, his stirring brought blessings to the soil. The fields became more fertile after his movements, the rains came at proper times, and the crops grew abundant. Farmers understood that Degei’s restlessness could be a gift, his shaking loosening the earth and making it ready to receive seeds and yield harvests. His moods governed the weather patterns storms that brought necessary rain or winds that could devastate if proper respect had not been shown.

But perhaps Degei’s most significant role emerged in relation to death and the afterlife. As supreme being, he became the ultimate judge of human souls, the arbiter who determined the fate of every person who passed from the living world. When Fijians died, their spirits did not simply cease to exist or wander aimlessly. Instead, they embarked on a journey to stand before Degei himself, the ancient serpent who had created their ancestors and now would measure the worth of their lives.

This judgment was not a simple matter of good versus evil in the way some other cultures conceived of afterlife sorting. Degei’s assessment was more nuanced, more tied to the specific values and social structures of Fijian society. He examined how well the deceased had fulfilled their obligations to family, to chief, to clan, to the gods themselves. He considered their behavior, their adherence to proper conduct, their respect for the sacred order that bound all things together.

For the fortunate few who had lived with exceptional honor, who had maintained their duties and shown proper respect throughout their lives, Degei offered passage to Burotu the blessed realm, a paradise of ancestors where spirits dwelled in peace and abundance. Burotu was not merely a reward but a recognition of lives well-lived according to Fijian values, a place where the honored dead could continue in spiritual harmony.

But most souls, even those who had lived reasonably good lives, were not destined for Burotu. The majority were consigned to Murimuria, the world-below, the vast underground realm where Degei himself dwelt. Murimuria was not simply a place of punishment, though it could contain suffering for those who had truly transgressed. Rather, it was a complex realm where spirits received their proper station based on how they had lived. Social hierarchies persisted even in death, with each spirit assigned a position appropriate to their earthly conduct and status.

This afterlife structure reinforced the importance of proper behavior during life. Chiefs and commoners alike knew that Degei was watching, that the supreme serpent god would one day judge them, that their eternal fate depended on maintaining the social and spiritual obligations that held Fijian society together. It was a powerful incentive for ethical behavior not out of abstract morality, but out of recognition that the creator who had shaped the islands and given life to humanity was also the final judge who would determine each soul’s ultimate destination.

The priests who served the gods and the chiefs who ruled the villages carried special responsibility in this divine order. They were intermediaries, in a sense, between Degei and the common people. Their proper conduct wasn’t merely about personal virtue it was about maintaining the relationship between the divine and mortal realms, about ensuring that Degei remained favorable toward the community as a whole. When chiefs and priests fulfilled their sacred duties, performed the correct rituals, and behaved with appropriate dignity, Degei blessed the people with fertile fields, favorable weather, and protection. When these obligations were neglected or corrupted, the consequences could be catastrophic earthquakes, storms, drought, and divine displeasure that affected entire villages.

Different villages throughout Fiji told variant tales about Degei’s specific acts of creation some claimed he created humans one way, others described different companion spirits or helper deities who assisted in the work of making the world. These variations reflected the rich oral tradition of Fijian culture, where stories adapted to local contexts while maintaining core truths. But certain elements remained consistent across all tellings: Degei was supreme, he created the islands through his movement, he gave essential gifts to humanity, he dwelt within the earth, his stirrings affected the physical world, and he judged the dead.

The serpent creator was thus simultaneously distant and intimate a cosmic being whose body had shaped geography, yet a present force whose moods could be felt in every tremor of the ground. He was generous benefactor who had given humans the tools for survival, yet stern judge who held each soul accountable. He was creator and destroyer, blessing and danger, the beginning of all things and the final authority at life’s end.

To live in Fiji was to live always in awareness of Degei his body beneath your feet, his judgment awaiting in the future, his gifts sustaining you in the present. The islands themselves were his creation, shaped by his divine form. The food that grew from the soil was his gift. The social order that governed daily life reflected his will. And when death came, as it came to all, the journey would lead inevitably to the coiled serpent god who had been there from the beginning and would remain long after, eternal and unchanging in the depths of the earth he had made.

Explore tales of ancestral spirits and island creation that connect people to the land and sea

The Moral Lesson

The legend of Degei teaches that creation carries responsibility both for the creator and the created. The supreme being who shapes the world remains intimately involved with it, judging how well his creation fulfills its purpose. For humans, the story emphasizes that proper conduct, respect for social obligations, and maintenance of spiritual practices are not optional virtues but essential duties that affect both earthly wellbeing and eternal fate. The landscape itself is sacred, formed by divine action, and must be treated with reverence. Most profoundly, Degei’s dual nature as generous creator and stern judge reminds us that gifts come with expectations, that authority must be earned through right behavior, and that the same power that blesses can also demand accountability.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Degei in Fijian mythology and what is his significance? A1: Degei is the supreme being in Fijian tradition a divine serpent god who created the Fijian islands, shaped the landscape, and brought forth humanity. He is simultaneously creator, provider, and ultimate judge of souls. Degei gave essential gifts like yams and taro to the first Fijians and established the rituals and social structures that govern proper relationships between humans and the divine realm.

Q2: How did Degei create the Fijian islands according to the legend? A2: Degei created the islands through his movement as a cosmic serpent. As his massive, ringed body coiled and turned through the primordial waters, mountains rose where he curved, valleys formed where he rested, and coral reefs bloomed where his tail dragged across the seafloor. The physical geography of Fiji is thus a direct result of the creator serpent’s wandering, with the landscape shaped by his divine form.

Q3: What transformation did Degei undergo after creating the world? A3: After actively creating the islands and humanity, Degei underwent a transformation from restless wanderer to earthbound deity. He descended into the ground, coiling his body deep within the earth with his tail buried in the depths. He became not just a god who visited the land, but a living presence within the earth itself, dwelling in the subterranean realm from which he continues to influence the world above.

Q4: How does Degei manifest his power from beneath the earth? A4: From his underground dwelling, Degei manifests power through earthquakes when the great serpent stirs or shifts position, the ground trembles. These movements aren’t always destructive; they often bring blessings by making fields more fertile and bringing proper rains. Degei’s moods also govern weather patterns, with storms and favorable conditions reflecting his disposition toward the people and their conduct.

Q5: What happens to Fijian souls after death according to Degei’s judgment? A5: When Fijians die, their spirits travel to stand before Degei for judgment. The serpent god examines how well they fulfilled their social and spiritual obligations during life. A fortunate few who lived with exceptional honor are granted passage to Burotu, the blessed realm of ancestors. Most souls are consigned to Murimuria, the world-below where Degei dwells, receiving positions appropriate to their earthly conduct not purely punishment, but proper station based on how they lived.

Q6: Why is proper conduct by chiefs and priests especially important in relation to Degei? A6: Chiefs and priests serve as intermediaries between Degei and the people, holding special responsibility for maintaining the relationship between mortal and divine realms. Their proper conduct and performance of correct rituals directly influence Degei’s favor toward the entire community. When these leaders fulfill their sacred duties, Degei blesses the people with fertility, favorable weather, and protection. When obligations are neglected, the entire community may suffer earthquakes, storms, drought, and divine displeasure.

Source: Adapted from Fijian oral tradition and mythology as preserved in ethnographic records and cultural documentation of Fijian cosmology and religious beliefs.

Cultural Origin: Fijian Mythology, Republic of Fiji, South Pacific