In the ancient days of the Solomon Islands, where the Roviana Lagoon stretched like a mirror between earth and sky, there existed a cave whose entrance resembled a sleeping eye. Mangroves stood sentinel along the water’s edge, their roots twisted deep into the mud like the fingers of old gods. The lagoon itself was a living thing sometimes gentle as a mother’s hand, sometimes wild as a warrior’s heart.

From the depths of this cave, on a morning when mist clung to the water like breath, six brothers emerged. They were not born of woman, but of the rock itself formed from the volcanic stone and the prayers of the land. Their skin was warm and damp, as if the earth had labored through the night to bring them forth. They were children of stone and sea, and their purpose would shape the fate of every voyager who dared challenge the ocean.

Click to read all Melanesian Folktales — rich oral storytelling from Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu

Tiola was the eldest among them. When he turned his gaze upon his brothers, they found courage pooling in their chests like floodwater. When he spoke, his words carried the weight of mountains. When he walked, the earth seemed to recognize him as its own son. The other five followed him as naturally as rivers follow valleys, trusting in the wisdom that seemed to pour from him like light from the sun.

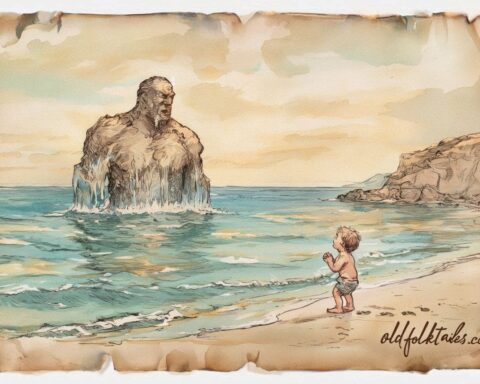

On their first morning in the world of air and water, the brothers stood upon the shoreline, their feet sinking slightly into the black volcanic sand. Before them, the Pacific Ocean rolled forward with the curiosity of a child discovering something new. The waves reached toward their toes, retreated, then reached again testing these strange new beings who stood at the threshold between land and sea.

The brothers had no canoe yet, no vessel to carry them across the vastness that called to them. Tiola gazed out at the horizon, where sky and water became one seamless blue. He saw not beauty alone, but danger. He saw the ocean’s vast open throat, lined with the teeth of coral reefs and sudden storms. He saw invisible currents that could pull a man down to where light dies. And in his heart, he feared for his people those who would come after, who would need to cross these waters to fish, to trade, to visit distant islands where family dwelt.

The ocean hungered for knowledge, for respect, for acknowledgment. Tiola understood this in his bones.

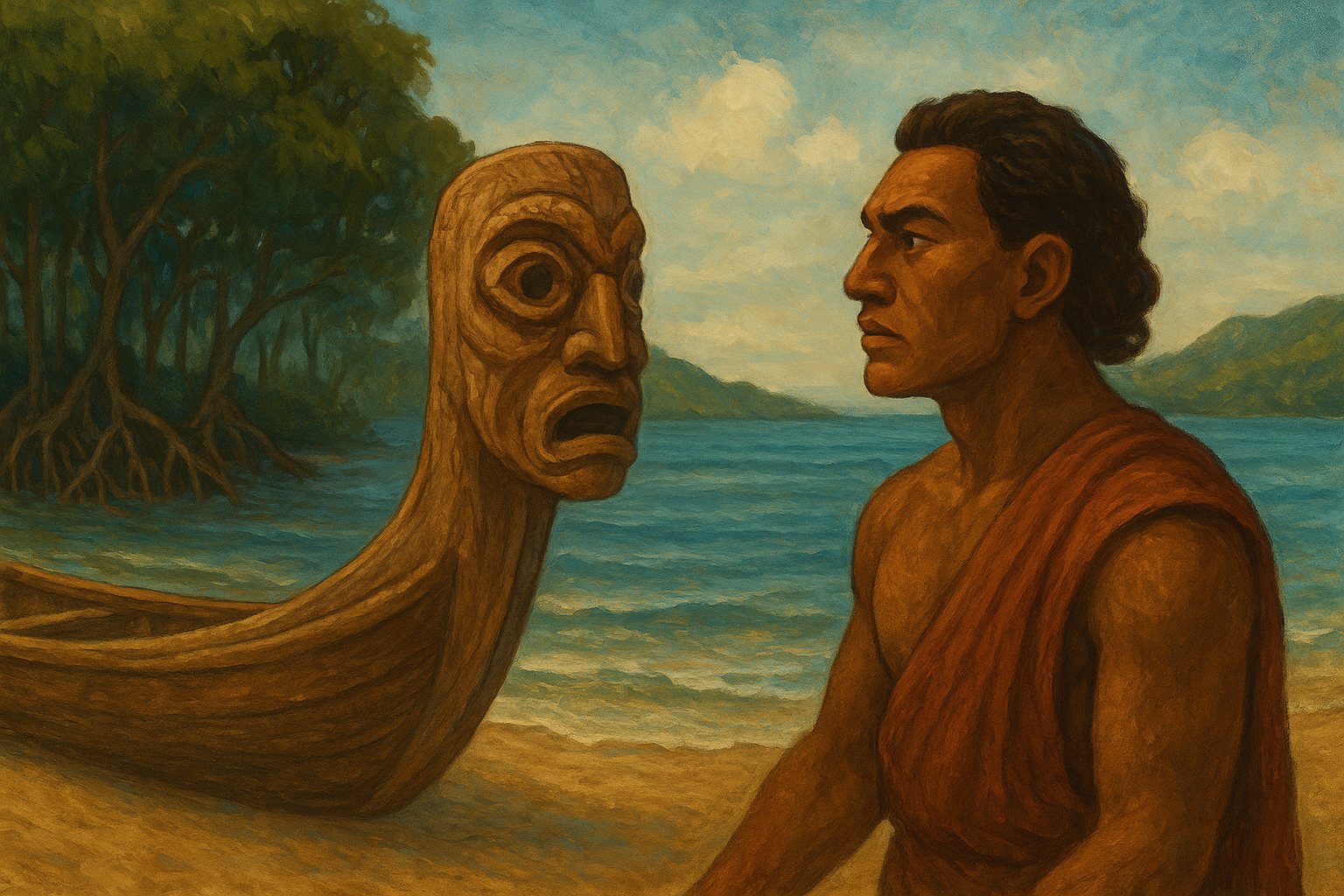

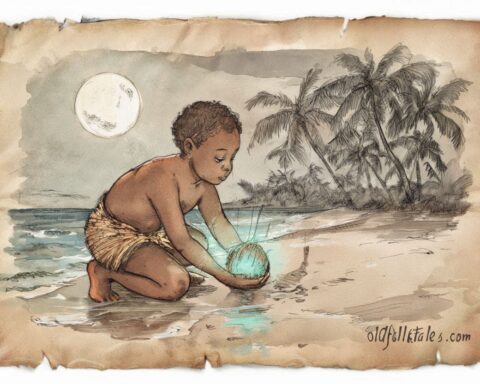

For days, he walked the shoreline, searching. Then he found it a piece of driftwood, smooth and salt-bleached, curved like a question mark by years of wave and tide. He sat with it for a long time, feeling its weight, understanding its grain. Then he began to carve.

With stone tools and patience, Tiola carved his own face into the wood. He gave it eyes wide as moons, always watching, never sleeping. He carved the mouth open as if calling to the wind, as if speaking words of protection that would echo across the water. He carved hands reaching forward not in supplication, but in readiness, poised to catch danger before it could strike the vessel, before it could touch those who sailed.

When the carving was complete, Tiola held it up to the morning light. It was his face, yet not his face. It was every protector, every ancestor, every spirit that had ever kept watch over travelers. “This,” he told his brothers, “is so that my wisdom might travel beyond my own life. So that even when I return to stone, my watching will continue.”

He fastened the carving to the prow of their first canoe, binding it with sinnet cord made from coconut fiber, sealing it with prayers and intention. When they pushed the canoe into the lagoon, something miraculous occurred. The waves, which had been choppy and uncertain, seemed to bow before the watching face. The water parted more smoothly. The canoe cut through the surface like a knife through silk.

Word of Tiola’s magic spread like fire through dry grass. Hunters who mounted the carved face on their canoes returned safely, their boats heavy with fish. Surfers found that the prow would strike hidden rocks first, warning them away before their bodies could be broken. The carved face became a companion to the sea speaking to it in a language older than words, negotiating safe passage for those who honored both the carving and the waters.

Other men, seeing this protection, began to copy Tiola’s creation. They carved their own faces, their own watching spirits, each one slightly different but all bearing the same essential features: wide eyes that never closed, open mouth calling to the elements, hands stretched forward in eternal vigilance. These guardians came to be called Nguzu Nguzu protectors who kept company with the sea, intermediaries between human ambition and oceanic power.

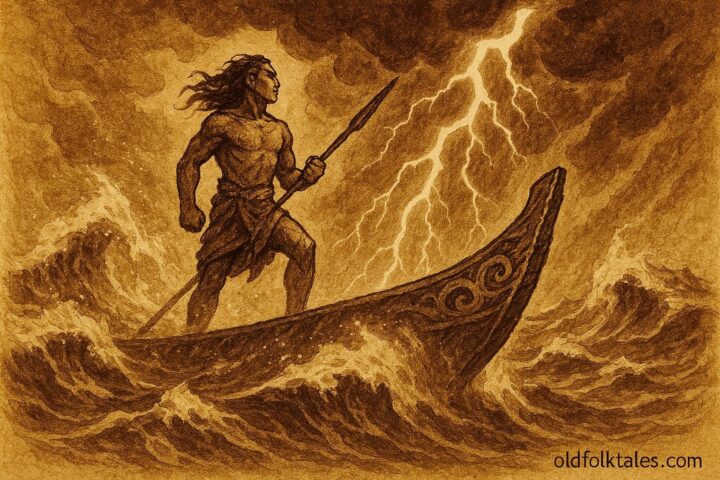

When storms gathered on the horizon, darkening the sky with their anger, the people would rush to their canoes. They would place their hands on the Nguzu Nguzu and shout to it telling it the names of their chiefs, reciting the names of their grandmothers and grandfathers, anchoring themselves to lineage and land even as they prepared to face the chaos of wind and wave. The carved face listened. The carved face remembered. And the boats, more often than not, rode steady through the tempest.

Tiola himself eventually returned to stone, as all who come from stone must. But his legacy remained on every prow, in every harbor, watching with eyes that never closed. The Nguzu Nguzu became more than decoration it became identity, protection, and prayer carved into permanence.

Explore tales of ancestral spirits and island creation that connect people to the land and sea

The Moral Lesson

Tiola’s story teaches us that true protection comes from wisdom combined with love and intention. A small thing a carved face, a thoughtful gesture, a word of care when created with genuine devotion, can hold us steady against life’s greatest storms. Our ancestors’ wisdom, when honored and carried forward, becomes a guardian spirit that guides us through dangerous waters. The Nguzu Nguzu reminds us that we are never truly alone when we carry forward the protective love of those who came before us.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was Tiola and how was he born in the Solomon Islands legend? A: Tiola was the eldest of six brothers who emerged from a cave in the Roviana Lagoon. They were not born of human parents but formed from volcanic rock itself, described as children of stone and sea. Tiola was recognized as a leader whose gaze gave his brothers courage and whose wisdom would shape the protective traditions of ocean voyagers.

Q2: What is the Nguzu Nguzu and why did Tiola create it? A: The Nguzu Nguzu is a carved wooden figurehead featuring a face with wide eyes, an open mouth, and hands reaching forward. Tiola created the first Nguzu Nguzu from driftwood to protect his people who would need to cross dangerous ocean waters. He carved his own face into it so that his protective wisdom could continue beyond his lifetime, serving as a guardian spirit for canoes.

Q3: What specific features does the Nguzu Nguzu carving include and what do they symbolize? A: The Nguzu Nguzu has three key features: eyes wide as moons (representing constant vigilance and watchfulness), an open mouth (symbolizing the calling to wind and spirits for protection), and hands reaching forward (representing the readiness to catch or deflect danger before it reaches the vessel or its passengers).

Q4: How did people use the Nguzu Nguzu during storms in Roviana Lagoon tradition? A: During storms, people would approach their canoes and speak directly to the Nguzu Nguzu, telling it the names of their chiefs and their grandmothers. This practice anchored them to their lineage and land while seeking protection. The carved face was believed to listen and help the boats ride steady through tempests.

Q5: What is the cultural origin and significance of the Nguzu Nguzu in Solomon Islands heritage? A: The Nguzu Nguzu originates from the Roviana Lagoon region of the Solomon Islands in Melanesia. It represents a crucial element of traditional seafaring culture, serving as both practical maritime protection and spiritual guardian. The figurehead embodies ancestral wisdom and the relationship between islanders and the ocean that sustains them.

Q6: What happened after Tiola first attached his carving to the canoe prow? A: When Tiola attached his carved face to the first canoe, the waters responded remarkablythe choppy waves seemed to bow before the watching face, and the canoe cut smoothly through the water. Hunters returned safely, surfers were warned of hidden rocks, and the success of this protection led other men throughout the region to carve their own Nguzu Nguzu for their vessels.

Source: Adapted from oral traditions of the Roviana Lagoon people, documented in ethnographic studies of Solomon Islands maritime culture, including references in The Art of the Pacific Islands by Peter H. Buck (Yale University Press).

Cultural Origin: Roviana Lagoon, Western Province, Solomon Islands, Melanesi